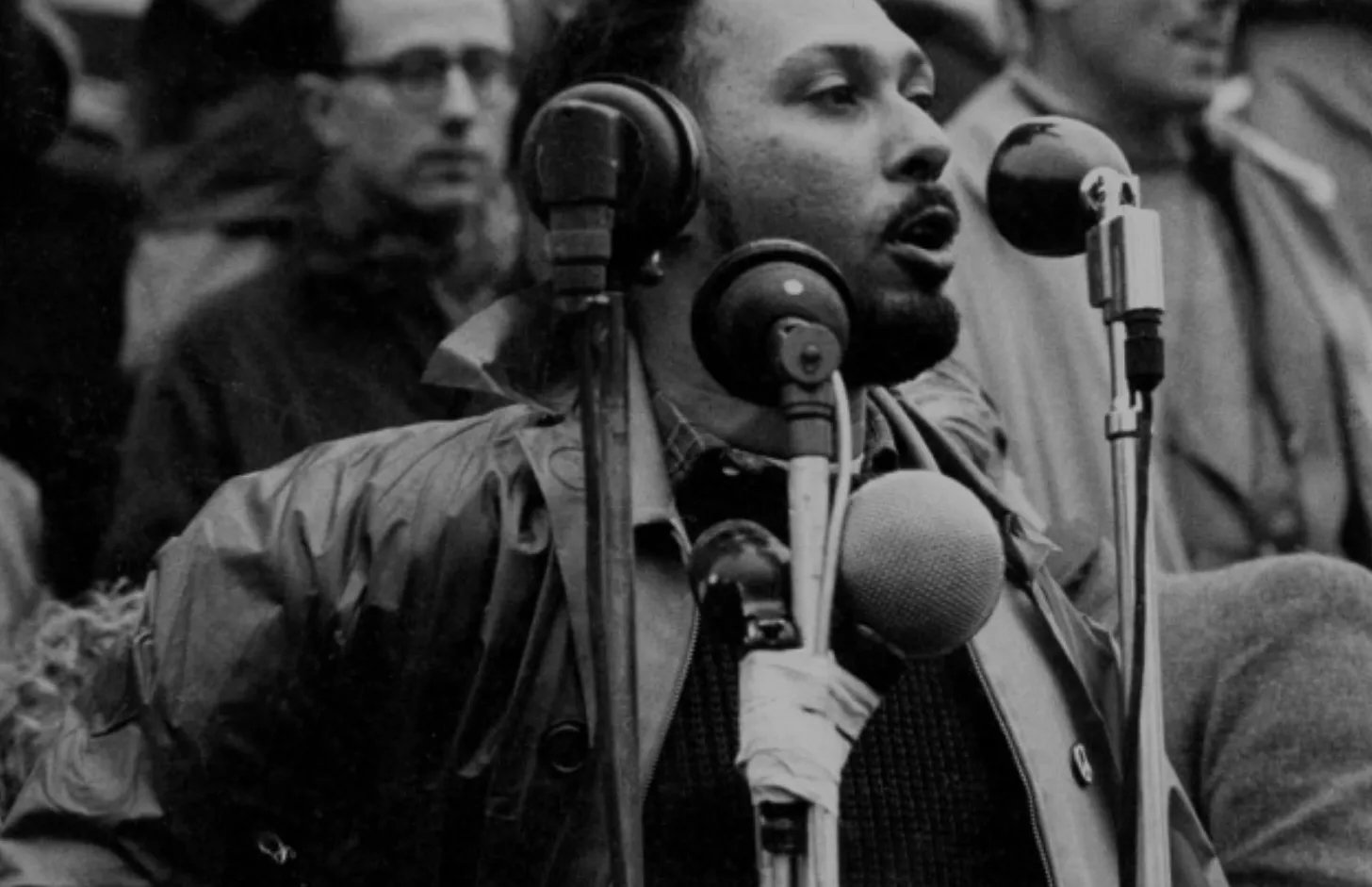

In these troubling times, we should return to Stuart Hall, a remarkable political thinker and cultural analyst.

Stuart Hall (1932-2014), born in Jamaica and educated at Oxford University, was one of the key cultural theorists, Marxist sociologists, and leftist thinkers in the postwar era. Hall is particularly known for concepts like encoding/decoding and authoritarian populism, and for his interest in studying conjunctures (the totality of societal situations); he is also known for his critical analyses of Thatcherism in the 1980s and studies of popular culture, identity, and race/ethnicity, and for helping establish cultural studies as a distinctive subdiscipline.

As a Marxist, Hall was concerned with economic conditions, but in his works, he avoided a reductive class determinism or economism (the excessive causal emphasis on class and economics), allowing instead for the autonomy of the political field, the state, the media and realm of culture. The concept of conjuncture was important to him in this respect: Hall repeatedly tried—particularly in the late 1970s and 1980s—to understand the totality of Britain’s political, economic, cultural, and social situation. Rather than fall back on formulaic concepts, Hall attempted to ground his analyses in the “specificity of the present.”[1]

This analytical approach was inspired by Lenin’s emphasis on the importance of “concrete analyses of concrete situations,” and Hall also drew on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony and the Althusser’s concept of ideological state apparatuses and interpellation. Hall’s attempts to understand a society were always grounded in concrete facts “from below,” but sensitized to power relations and the effects of power within such relations. Hall also contributed to making Marxism more attuned to the political, cultural, and identitarian dimensions of social life; the Marxism he initially had encountered in the postwar period had been “a very economistic Marxism,” as Hall said in a later interview.[2]

Hall was also a prolific writer: A bibliography listing the titles of his works alone runs to 79 pages. In the 1950s, he cofounded the New Left Review, an influential journal that remains an arena for important debates to the global Anglophone left. Among his best-known publications is his 1978 book Policing the Crisis, written with four other scholars, which on the surface is a study of “law and order” politics in Britain in the late 1970s, but which is more deeply about ideology, conflict, control, and the effects of crisis on the state; Hall saw an increasingly heavy-handed British state rise up in the face of growing crisis. He also wrote dozens of articles and essays on everything from popular culture to ethnic identity and Thatcherism throughout his lengthy writing career.

Background

Hall spent the first part of his life in Jamaica. In his memoir, Familiar Stranger, he describes a middle-class upbringing in the capital city of Kingston. His father rose through the ranks of the (otherwise notorious) multinational United Fruit Company to become chief accountant; his maternal family considered themselves descendants of plantation and slave owners who admired the British (colonial) education system.[3] The young Hall was sent to the private secondary school Jamaica College, established in 1789 to educate the Caribbean colony’s elite children. There Hall received a “classically British formal education.”[4] A gifted student, in 1951 he received a prestigious Rhodes Scholarship and was admitted to Merton College at Oxford. The nearly 700-year-old college was one of the British Empire’s central elite institutions of higher education—and one of the oldest universities in the world, if not the oldest.

Later in life, Hall emphasized that although his time at Oxford had been a formative intellectual experience, he disliked the overall “spirit of Oxford”: The university’s position in the national, and therefore imperial, system of power troubled him. In later interviews, Hall emphasized how “Oxford connections” lifted people undeservedly into elite positions in British society.[5] Perhaps precisely because of his ambiguity concerning Oxford’s “intellectual and cultural power,” and the “nerve-racking experience” of encountering a form of (culturally imposed) “absolute superiority” that he encountered there, Hall was drawn to leftwing politics during his student years. It was on the left that Hall found his second home. His was assuredly not a Soviet-style Marxism, but a “non-aligned left,” or a leftism that refused to take sides in the Cold War.[6] In the mid-1950s, there were still high hopes for the so-called Non-Aligned Movement and the possibility of a “‘third force’ in global politics.”[7] In 1955, the first Bandung Conference took place—named after the Indonesian city that hosted it—where representatives from 29 African and Asian countries met to discuss the possible role of a “third world” caught between the Scylla and Charybdis of the U.S. and Soviet empires, respectively. But the “utopian” vision of nonalignment failed to produce lasting results: “We didn’t foresee at all how the global imperatives of the Cold War would overwhelm the liberatory promise of decolonization,” Hall wrote.

As a colonial subject, Hall could not fit into establishment institutions with the same ease as his fellow cohort of English students. Even in Jamaica, one of his editors writes, Hall was well aware of the fact that he was the “blackest member of his own family,” and he later developed the term pigmentocracy to describe the role of color gradations in the structure of power relations in Jamaican society. His sense of ethnoracial otherness was, of course, even stronger in largely white England:

Three months at Oxford persuaded me that it was not my home. I’m not English and I never will be. The life I have lived is one of partial displacement. I came to England as a means of escape, and it was a failure.[8]

Even within Oxford’s leftwing political sphere, Hall felt a lack of affinity with the postwar hegemonic British Labour Party: “The ethos of Oxford Labour politics was unremittingly white and English.”[9] Instead, Hall was drawn into a group calling itself The Socialist Club, a gathering of “ex-Communists, Trotskyists and assorted socialists, as well as a variety of independently minded Labour supporters.”

The second half of the 1950s was a dramatic time, with the Soviet Union’s invasion of Hungary in 1956 and the Suez Crisis of the same year being two key events. Tariq Ali is careful to describe Hall not as a child of 1968—Hall was too old for the “year of revolution” to have played a formative role—but rather as a “1956-er,” when Western Marxists were forced to reckon with the Soviet invasion of Hungary but were also galvanized by the Suez Crisis and the British, French, and Israeli invasion of Egypt.

Hall became an important figure in what became known as “the new left,” which, among other things, attempted to chart out a course between Soviet communism and Western capitalism. For Hall, much of this meant throwing himself into intellectual activity. Journals remained important platforms. In 1957, together with Charles Taylor, later a renowned philosopher, Hall founded the journal Universities and Left Review (ULR). Two years later, ULR merged with another journal established by the historian E. P. Thompson, New Reasoner, to form New Left Review (NLR).

Collective Thought

Hall was an exceptionally community-oriented thinker. His book Policing the Crisis counts five co-authors. Hall was one of the co-founders of the influential research center, the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at the University of Birmingham in the 1960s. He led the center for a decade from 1969 to 1979 and made it the birthplace of the so-called ‘Birmingham School of Cultural Studies’; forming a ‘school’ demonstrates a willingness to enter into reciprocal relationships with others.

Hall is an example of what sociologist Pierre Bourdieu called the “collective intellectual.” Bourdieu used the term in contrast with the philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre’s notion of the “total intellectual,” who was happy to intervene, often on their own, in all manner of social and political issues. Bourdieu believed this was a fundamentally flawed way of conducting intellectual activity: The complexity of society demands associations of specialized thinkers, each of whom can shed light on a particular aspect of society. But more importantly, Bourdieu understood that powerful social forces were working to limit the autonomy of research; only research collectives would be able to “defend their own autonomy.”[10] Some of Hall’s former colleagues at CCCS refer to a feature of Hall that they call a “dialogical pedagogy” that was “fundamental to the work culture [Hall] established” at the Birmingham center.[11] Thinking happens along with others.

Interests

In the 1960s, Hall was a driving force behind what became known as cultural studies. In 1964, Hall cofounded the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at Birmingham University, which he also directed from 1969 to 1979. Later in his life, Hall explained the shift towards cultural studies with a confrontation with a shortcoming of the Marxism of the time:

I got involved in cultural studies because I didn’t think life was purely economically determined. I took all this up as an argument with economic determinism. I lived my life as an argument with Marxism, and with neoliberalism. Their point is that, in the last instance, economy will determine it. But when is the last instance? If you’re analyzing the present conjuncture, you can’t start and end at the economy. It is necessary, but insufficient.

In an early articles from 1959, “Politics of Adolescence?”, Hall shows an emerging interest in, and sympathy with, youth culture.[12] While the British establishment viewed with growing alarm a number of “subcultural” youth phenomena like the “teddy boys” or conflicts between “mods” and “rockers”—later studied by the sociologist Stanley Cohen in a classic book as an example of “moral panic”—Hall took a more positive approach. For him, there is a progressive potential to be unearthed in youth culture, especially of the working class: “Instinctively, young working class people are radical.” Rare in the context of the 1950s, Hall tried to understand young people on their own terms. He saw in the anti-nuclear movement, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, a sign that young people were not apathetic, but instead politically engaged, albeit outside political party structures and so accorded less recognition by the left at the time.

Encoding and decoding

This openness to the new led Hall to become one of the earliest serious analysts of television. The article “Encoding and Decoding in the Television Discourse” has become a classic in the field of media studies, with over 16,000 citations on Google Scholar, a clear sign of its enormous influence. Hall’s main idea is that cultural messages are packaged, or “encoded,” by a sender and then unpacked, or “decoded,” by an audience, but that this is a potentially fallible process, where the receiver may choose, or at least end up, interpreting the message in a way that violates the sender’s wishes. A sender may want to encourage a particular reading, but all messages carry with them a chance of being misunderstood, misread, or—better yet—read against the grain of original intent. Against the idea that the masses are fed mass-produced cultural products and absorb them in zombie-like fashion, Hall allows for the possibility that audiences can form their own interpretations and opinions.

“Race” and ethnicity

In a series of lectures on race, ethnicity, and the nation, delivered at Harvard University in 1993 but not published until 2017,[13] Hall proposes a discursive theorization of the concepts of race and ethnicity. He explores how “race is a cultural and historical, not biological, fact” and in which ways “race is a discursive construct, a sliding signifier.” But “race” as such has no real, underlying biological reality; racial categories have no meaning or “reality” in and of themselves but are charged with various associations in different social contexts. Physical signs—skin color, nose and facial shape, hair type, and so on—are saturated with social meaning, creating differential distributions of resources and power in various social orders across history. Race remains, however, a “myth,” as the anthropologist Robert Sussman later notes, and is hence a profoundly “unscientific idea,” which nevertheless has sociological implications by virtue of the power placed behind racial divisions, or discursive formations, that different societies operate with.

Hall also argues that notions of cultural differences, or ethnicity, today play much the same role as racial differences did in times past, and that ethnicity with its seemingly harmless emphasis on cultural traits nevertheless tends to “slide” onto an essentializing track—what Hall calls a “transcendental fix in common blood, inheritance, and ancestry, all of which gives ethnicity an originary foundation in nature that puts it beyond the reach of history.”[14] In this way, Hall clearly gave witness to the rise of what is sometimes called cultural racism.

Thatcherism

In 1979, the Conservative politician Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister of Great Britain. Until her resignation in 1990, she led the country out of the social-democratic era regnant since the Second World War, where the great popular mobilization, “the people’s war,” had been replaced by “the people’s peace,” involving major welfare-state reforms such as free health care under the National Health Service (NHS), the nationalization of key industries, comprehensive social welfare benefits and relatively strong redistributive policies. The Thatcher era signified the end of this form of social-democratic ascendancy; it was a polarized time marked by the triumph of political reaction, from the heightened patriotic sentiment against a common enemy during the Falklands War with Argentina to Thatcher’s targeted campaign against striking coal miners in 1984-1985 and the privatization of state-controlled enterprises, aided by Thatcher’s own “neoliberal” think tank, the Centre for Policy Studies, which she had co-founded the previous decade.

In Policing the Crisis, published the year before Thatcher came to power, Hall and his co-authors studied an apparently narrow criminological question: Why did a series of muggings in Britain become the subject of heated public debate, frenzied media reporting, and a subsequent tightening of the screws of criminal justice?[15] But the analysis burrowed deeper down to the root of the British state and social order.

Amid economic crisis, young black men came to constitute the “perfect” targets in this political moment, concentrating racialized and class-inflected fears around a potent category of social denigration, far beyond the real or “objective” threat muggings might pose to public safety. But Hall and his colleagues saw in the emergence of what they called a “racialized law and order politics”[16] the contours of a new social order, a new conjuncture, radically different from the social-democratic communitarianism characterizing the “golden age” of the welfare state in the three decades post-1945. In the moral panic surrounding street crime perpetrated by young black men, Hall and his colleagues saw the emergence of what they termed authoritarian populism. The book was prophetic, too, in its predictions of “the collapse of the social democratic consensus” and “the rise of the radical right.”[17]

Social democracy had been a successful political-economic arrangement, allowing broad sections of society to take part in economic productivity gains, while tamping down social contradictions; but as this order began to break down, it became increasingly clear that various “populist” moral crises—often revolving around crime and punishment—were being mobilized in its stead. With the essay collection, The Hard Road to Renewal, published in 1988, it is clear that “Thatcherism” stands for Hall as a key sociopolitical concept. Hall views Thatcher as an authoritarian populist: Thatcher seemed to need the heavy hand of the state to bolster her fluctuating popularity. The concept of authoritarian populism probably remains underspecified, which Hall also acknowledged. But the concept captures something essentially true, still relevant today: “It’s not quite fascism but it has the same structure as fascism does.”[18]

States today solve many of their problems by selecting an external enemy, or an internal enemy that is externalized, to hammer away at, either symbolically or materially, whether that means forcibly detaining families in camps on the Mexican border (under Trump), or deporting asylum seekers to Rwanda (advocated by three consecutive Tory Prime Ministers—Johnson, Truss, and Sunak), or engaging in repeated cycles of tough-on-crime rhetoric and law-and-order policies. Hall was an early and articulate exponent of this peculiar political dynamic, which seems to manifest itself all the more aggressively as states cede control of instruments of economic intervention.

Contradictions and Post-Neoliberalism

Hall had a unique social trajectory. He embodied a series of tensions and outright contradictions, related to class (a relatively privileged middle-class background in colonial, impoverished Jamaica), colonialism (a Caribbean immigrant in white Britain), ideology (a socialist amidst the Oxford intelligentsia), and theory (a culturally-oriented theorist stressing contingency among orthodox Marxists).

But contradictions can be productive. Hall remained a prolific, innovative intellectual for over half a century. He also combined the political and the academic in a way that runs counter to the ethos of contemporary academe. In times of political reaction, we should return to Hall—as someone who forged a way through academic spaces with his ideals not only intact but his intellectual tools sharpened, honed, and refined.

Towards the end of his life, Hall joined with others to publish The Kilburn Manifesto, an attempt to think beyond both Thatcherism and Blair’s New Labour. As in his writings in the late 1970s, where Hall sensed the withering away of social democracy, Hall here seemed to foretell the ways in which neoliberal dogmas would no longer seem quite so self-evidently true by the 2020s. Virtually no other political commentator was writing as early as the year 2015 about a world “After Neoliberalism?”, to quote the manifesto’s title, published at a time when neoliberalism seemed to reign supreme. Once again, Hall was five or ten years ahead of his time.

Although Hall searched for patterns and structures in the social order and was painfully aware of the crushing weight of power and domination in capitalist modernity, he nevertheless believed in the fundamental openness of history and the possibility of political change. For him, a conjuncture was always characterized by contingency. As Hall noted in one of his lectures: “If you don’t agree that there is a degree of openness or contingency to every historical conjuncture, you don’t believe in politics. You don’t believe that anything can be done.”[19] The world can always be remade.

Even when Hall presented his apparently bleak analyses, he often seemed to do so with a gleam in his eye and a faintly ironic smile—as if to suggest that even if everything is impossible, the situation is still far from hopeless.

This essay is an abbreviated, translated version of an essay forthcoming in Norwegian in an edited volume titled Sosial teori (Social Theory).

Book Recommendations

· Selected Political Writings: The Great Moving Right Show and Other Essays (Duke University Press, 2017). An excellent synoptic overview over Hall’s political interventions and analyses.

· Familiar Stranger. A Life between Two Islands (Duke University Press/Penguin, 2018). A moving portrait of a life lived in parallax between “two islands”: Jamaica and Britain.

Footnotes

1 Gilbert, J. (2019). “This conjuncture: For Stuart Hall.” New Formations, 96(1), 5-37, p. 5.

2 Hall, S., Segal, L., & Osborne, P. (1997). “Stuart Hall: Culture and power.” Radical Philosophy 86 (Nov/Dec): 24-41.

3 For a full autobiographical account, see Hall, S. (2017). Familiar Stranger: A Life Between Two Islands. Durham: Duke University Press.

4 Morley, D. (2019) “General introduction.” In: Morley, D. (ed.), Stuart Hall: Essential Essays Vol. 2: Identity and Diaspora. Durham: Duke University Press, p. 1.

5 Jaggi, M. (2009). “Personally speaking: A long conversation with Stuart Hall,” p. 19.

6 Hall, Familiar Stranger, p. 235.

7 Hall, Familiar Stranger, p. 232.

8 Williams, Z. (2012). “The Saturday interview: Stuart Hall.” The Guardian, February 11, 2012.

9 Hall, Familiar Stranger, p. 253.

10 Bourdieu, P., Sapiro, G., & McHale, B. (1991). “Fourth lecture. Universal corporatism: The role of intellectuals in the modern world.” Poetics Today, 12(4), 655-669, p. 660.

11 Hall, S. (2019). Essential Essays, Volume 1: Foundations of cultural studies (Morley, D., ed.). Durham: Duke University Press Books, p. 339.

12 Hall, S. (1959) “Politics of adolescence?”. Universities & Left Review, 6 (Spring 1959), 2-4.

13 Hall, S. (2017). The Fateful Triangle: Race, Ethnicity, Nation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

14 Hall, The Fateful Triangle, pp. 108-109.

15 Hall, S., Critcher, C., Jefferson, T., Clarke, J., & Roberts, B. (1978/2013). Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order (2nd ed.). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

16 Hall et al., Policing the Crisis, p. 396.

17 Hall, S. (1985). “Authoritarian populism: A reply to Jessop et al.” New Left Review May/June I/151: 115-124, p. 116.

18 Jaggi, “Personally speaking”, p. 35.

19 Media Education Foundation (2021). “Studying the Conjuncture - Stuart Hall: Through the Prism of an Intellectual Life” [video transcript].